Who Did Hair Fashion in the 50 and 60 1950s Hair and Makeup

The 1950s were a decade known for experimentation with new styles and civilisation. Following Globe State of war Two and the austerity years of the post-war period, the 1950s were a time of comparative prosperity, which influenced fashion and the concept of glamour. Hairstylists invented new hairstyles for wealthy patrons. Influential hairstylists of the period include Sydney Guilaroff, Alexandre of Paris and Raymond Bessone, who took French hair fashion to Hollywood, New York and London, popularising the pickle cut, the pixie cutting and bouffant hairstyles.

The American film manufacture and the popular music industry influenced hairstyles around the globe, both in mainstream manner and teenage sub-culture. With the advent of the rock music industry, teenage culture and mode became increasingly significant and distinctive from mainstream fashion, with American style beingness imitated in Europe, Asia, Australasia and South America. Teenage girls around the world wore their pilus in ponytails while teenage boys wore coiffure cuts, the more rebellious among them favouring "greaser" comb-backs.

The development of hair-styling products, particularly setting sprays, hair-oil and hair-cream, influenced the way hair was styled and the way people around the world wore their hair day to day. Women'south hairstyles of the 1950s were in full general less ornate and more breezy than those of the 1940s, with a "natural" look being favoured, even if information technology was achieved past perming, setting, styling and spraying. Mature men's hairstyles were e'er short and dandy, and they were generally maintained with hair-oil. Even among "rebellious youth" with longer, greased hair, carrying a comb and maintaining the hairstyle was office of the culture.

Male fashion [edit]

Popular music and moving-picture show stars had a major influence on 1950s hairstyles and fashion. Elvis Presley and James Dean had a swell influence on the high quiff-pompadour greased-up style or slicked-back mode for men with heavy use of Brylcreem or pomade. The pompadour was a fashion trend in the 1950s, peculiarly among male rockabilly artists and actors. A variation of this was the duck's ass (or in the UK "duck'southward arse"), likewise called the "duck's tail", the "ducktail", or simply the D.A.[1]

This hairstyle was originally adult by Joe Cerello in 1940. Cerello's clients later included motion-picture show celebrities similar Elvis Presley and James Dean.[2] Frank Sinatra posed in a modified D.A. style of hair. This mode required that the hair be combed back around the sides of the caput. The molar edge of a comb was then used to ascertain a central part running from the crown to the nape at the back of the head, resembling, to many, the rear end of a duck. The hair on the pinnacle forepart of the head was either deliberately disarrayed so that untidy strands hung downwards over the brow, or combed up and then curled downwards into an "elephant'south trunk" which might hang down as far as the peak of the nose. The sides were styled to resemble the folded wings of the duck, often with heavy sideburns.[3]

A variant of the duck's tail style, known as "the Detroit", consisted of the long back and sides combined with a flattop. In California, the top pilus was allowed to abound longer and combed into a wavelike pompadour shape known as a "breaker". The duck's tail became an emblematic coiffure of disaffected young males across the English-speaking earth during the 1950s, a sign of rebellious youth and of a "bad male child" epitome.[1] [4] [5] The style was frowned upon by loftier school authorities, who often imposed limitations on male hair length as function of their dress codes.[six] Nevertheless, the style was widely copied past men of all ages.[2]

The regular haircut, side-parted with tapered dorsum and sides, was considered a clean cutting style and preferred by parents and school authorities in the Usa. The crew cut, flattop and ivy league were likewise popular, particularly among high school and college students.[7] The crew cutting style was derived from the military haircuts given to millions of draftees,[8] and was favored by men who wished to appear "institution" or mainstream.[ix] Daily applications of "butch wax" were used to make the short hair stand up straight up from the caput.[10] Celebrities favoring this fashion included Steve McQueen, Mickey Mantle and John Glenn. Crew cuts gradually declined in popularity by the cease of the decade; by the mid-1960s, long hair for men had become fashionable.[11] [12]

Black male entertainers chose to wear their hair in short and unstraightened styles.[thirteen]

In southeast Asia, a variation of the quiff that was popular was the "curry puff", styled by a bob of wavy hair but to a higher place the forehead.[xiv] "Geek chic" was a fashion trend for intellectual types, with a bouffant or greased-back hair and black spectacles, exhibited by the likes of Buddy Holly and Bill Evans.

It originally it was frequent in beach areas, like Hawaii and California.[ commendation needed ]

- Side part

-

- Long pompadour

-

-

-

- Coiffure cut and Ivy League

-

The Platters, 1950s, with variations of the crew cut and ivy league

Female fashion [edit]

Women generally emulated the hair styles and hair colors of popular film personalities and mode magazines; top models played a pivotal office in propagating the styles.[2] Alexandre of Paris had developed the beehive and artichoke styles seen on Grace Kelly, Jackie Kennedy, the Duchess of Windsor, Elizabeth Taylor, and Tippi Hedren.[15] Generally, a shorter bouffant style was favored by female movie stars, paving the style for the long hair tendency of the 1960s. Very brusk cropped hairstyles were fashionable in the early 1950s. By mid-decade, hats were worn less frequently, specially as fuller hairstyles like the short, curly "elfin cut" or the "Italian cut" or "poodle cut" and subsequently the bouffant and the beehive became fashionable (sometimes nicknamed B-52s for their similarity to the bulbous noses of the B-52 Stratofortress bomber).[xvi] Stars such every bit Marilyn Monroe, Connie Francis, Elizabeth Taylor and Audrey Hepburn usually wore their pilus short with high volume. In the poodle hairstyle, the hair is permed into tight curls, similar to the poodle'south curly hair (curling the hair involves time and effort). This style was popularized by Hollywood actresses similar Peggy Garner, Lucille Ball, Ann Sothern and Faye Emerson. In the mail-state of war prosperous 1950s, in particular, the bouffant hair style was the most dramatic and considered an platonic style in which droplets hairspray facilitated keeping large quantities of "backcombed or teased and frozen hair" in identify. This necessitated a regimen of daily hair care to go along the bouffant in place; curlers were worn to bed and frequent visits were made to the pilus stylist's salon. Mouseketeer Annette Funicello dramatically presented this hair style in the moving-picture show "Beach Party".[17]

Short, tight curls with a poodle cut known as "short bangs" were very pop, favored by women such equally offset lady Mamie Eisenhower.[ii] [12] Henna was a popular hair dye in the 1950s in the US; in the popular TV comedy series I Love Lucy, Lucille Brawl (according to her husband's statement) "used henna rinse to dye her chocolate-brown hair red."[two] The poodle cutting was too made popular by Audrey Hepburn. In the 1953 film Roman Vacation, Audrey Hepburn's character had short hair known as a "gamine-style" pixie cut, which accentuated her long neck, and which was copied by many women.[18] In the film Sabrina, her character appears initially in long plain hair while attending culinary school, but returns to her Paris domicile with a chic, short, face-framing "Paris hairstyle", which again was copied by many women. When the rage amidst women was for the "blond bombshell" pilus style, Hepburn stuck to her dark brown hair color and refused to dye her hair for any film.[2]

Mamie Eisenhower, wearing a short fringe "bangs", 1954

Jacqueline Kennedy wore a short hair mode for her wedding in 1953, while later on she sported a "bouffant"; together with the larger beehive and shorter chimera cutting, this became i of the most popular women's hairstyles of the 1950s.[2] Grace Kelly favored a mid-length bob style, too influential. There were exceptions, nevertheless, and some women, such as Bettie Page, favored long, straight dark locks and a fringe; such women were known equally "Crush girls".[12] In the mid-1950s, a high ponytail became popular with teenage girls, often tied with a scarf.[2] [xviii] The ponytail was seen on the beginning Barbie dolls, in 1959; a few years later Barbies with beehives appeared.[2] The "artichoke cut", which was invented by Jacques Dessange, was especially designed for Brigitte Bardot.[xi] Compact coiffures were pop in the 1950s as less importance was given to hairstyling, although a new wait was stylized by Christian Dior'southward fashion revolution later on the state of war.[11]

Products [edit]

In the 1950s, lotion shampoos with conditioning ingredients became popular precursors of the shampoo/conditioner rinse pairing of two decades subsequently. The Clairol advertizement campaign, "Does she ... or doesn't she?" boosted hair color production sales not just for their company, but across the hair dye manufacture.[19]

The bouffant style relied on the liberal utilize of hairspray to hold hair in place for a calendar week.[twenty] Hairspray lacquers of this era were of a different chemic formula than used today, and were more difficult to remove from the hair than today'south products.[21] But even less extreme styles, such as parting hair on the left and the right before pulling the bangs to i side, required holding the style in place with hairspray.[22] One ingredient in 1950s hair spray was vinyl chloride monomer; used as an alternative to chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), information technology was after establish to be both toxic and flammable.[23]

Hair gels, such equally Dippity-exercise, came in a multifariousness of forms such as spray or jelly, and were referred to as "setting gels".[twenty] African American hair products promised natural-looking hair to blackness women, with natural in this context divers as straight, soft, and smoothen; these products, such every bit Lustra-silk, were advertised to not be heavy, greasy or dissentious similar pressing oils and chemical relaxers of the past.[24]

Only a small amount of Brylcreem was needed to make a man's pilus shiny and stay in place; Brylcreem'due south tag line was "Brylcreem, a little dab'll practice ya."[25] It was likewise used by those who suffered from dandruff.[26] While the conk was still popular through the end of the decade, Isaac Hayes switched to going bald.[13] Hair growth products for men were showtime introduced in the 1950s, in Japan.[27]

Influence [edit]

The 1950s had a profound influence on mode and continues to be a strong influence in contemporary fashion. Some of the world's about famous fashion icons today such as Christina Aguilera, Katy Perry, and David Beckham regularly article of clothing their hair or indulge in a way of fashion clearly heavily influenced past that of the 1950s. Aguilera is influenced by Marilyn Monroe,[28] Beckham by Steve McQueen and James Dean.[29]

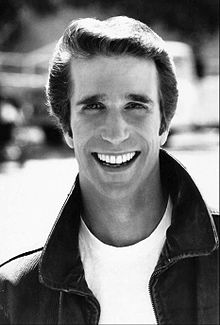

The pompadour style became popular among Italian Americans and the paradigm became an integral office of the Italian male stereotype in the 1970s in films such as Grease and television series such as Happy Days. The Fonz, played by Henry Winkler, with his greased pompadour, white T-shirt and leather jacket, has been cited as the "epitome of the 50s bad-boy cool".[thirty] In modernistic Japanese popular civilization, the pompadour is a stereotypical hairstyle frequently worn by gang members, thugs, members of the yakuza and its junior analogue bōsōzoku, and other similar groups such as the yankii (high-school hoodlums).[31] In Japan the manner is known equally the "Regent" hairstyle, and is often caricatured in various forms of entertainment media such as anime, manga, tv, and music videos.[32]

See also [edit]

- Hairstyles in the 1980s

- 1950s fashion

References [edit]

- ^ a b Peterson, Amy T.; Kellogg, Ann T. (2008). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Clothing Through American History 1900 to the Nowadays. ABC-CLIO. p. 53. ISBN978-0-313-33395-8 . Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ a b c d due east f g h i Sherrow, Victoria (2006). Encyclopedia of Pilus: A Cultural History . Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 192, 194, 206–208. ISBN978-0-313-33145-9 . Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ Augustyn, Heather; Marley, Cedella (27 September 2010). Ska: An Oral History. McFarland. p. 164. ISBN978-0-7864-6040-3 . Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ Clark, Terry Due north. (2004). The Metropolis Every bit an Entertainment Machine. Emerald Grouping Publishing. p. 163. ISBN978-0-7623-1060-nine . Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ Kubernik, Harvey (30 December 2006). Hollywood Shack Job: Rock Music in Movie and on Your Screen. UNM Press. p. 273. ISBN978-0-8263-3542-5 . Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ Calhoun, Craig; Sennett, Richard (2007). Practicing Cultures. New York: Routledge. p. 205. ISBN9781134126118.

- ^ How to foursquare flattop hair. Life Magazine. 12 November 1956. p. 149.

- ^ Browne, Ray B.; Browne, Pat (2001). The Guide to U.s.a. Popular Civilisation. The University of Wisconsin Press. p. 357. ISBN9780879728212.

- ^ Behnke, Alison Marie (2011). The Little Blackness Dress and Zoot Suits: Depression and Wartime Fashions from the Depression to the 1950s. Twenty-Get-go Century Books. p. 35. ISBN9780761380559.

- ^ Osceola, Holatte-Sutv Turwv (2011). Nokosee & Stormy. Palmetto Bug Books. p. 27. ISBN9780963449948.

- ^ a b c Steele, Valerie (xv November 2010). The Berg Companion to Way. Berg. p. 389. ISBN978-ane-84788-563-0 . Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ a b c Craats, Rennay (one Baronial 2001). History of The 1950s. Weigl Publishers Inc. pp. 36–37. ISBN978-1-930954-24-3 . Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ a b Byrd, Ayana; Tharps, Lori (12 Jan 2002). Pilus Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Pilus in America. Macmillan. pp. 88–. ISBN978-0-312-28322-3 . Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ^ Phua, Edward (1999). Sunny days of an urchin. Federal Publications. p. 29. ISBN978-981-01-2440-iii . Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ^ Moral, Tony Lee (28 September 2005). Hitchcock And the Making of Marnie. Scarecrow Press. pp. 71–. ISBN978-0-8108-5684-4 . Retrieved nineteen September 2012.

- ^ Patrick, Bethanne Kelly, and John Thompson, Henry Petroski (2009). An Uncommon History of Common Things. National Geographic. p. 206. ISBN978-1-4262-0420-3.

- ^ Brunell, Miriam Forman- (2001). Girlhood in America: An Encyclopedia, Book 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 355. ISBN9781576072066 . Retrieved xviii September 2012.

- ^ a b Rooney, Anne (1 May 2009). The 1950s and 1960s. Infobase Publishing. p. 56. ISBN978-one-60413-385-1 . Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ Loma, Daniel Delis (1 February 2002). Advertizement TO THE AMERICAN Woman . Ohio State University Printing. pp. 101, 103–. ISBN978-0-8142-0890-8 . Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ^ a b Willett, Julie (11 May 2010). The American Beauty Industry Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 137–. ISBN978-0-313-35949-1 . Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ^ Robbins, Clarence R. (2012). Chemical and Physical Behavior of Man Hair. Springer. pp. 779–. ISBN978-three-642-25611-0 . Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ^ Rudiger, Margit; Samson, Renate von (xxx June 1998). 388 Great Hairstyles . Sterling Publishing Visitor, Inc. pp. 21–. ISBN978-0-8069-9401-7 . Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ^ Siobhan, O'Connor (13 July 2010). No More Dirty Looks: The Truth about Your Dazzler Products--And the Ultimate Guide to Prophylactic and Make clean Cosmetics. Da Capo Printing. pp. 72–. ISBN978-0-7382-1418-4 . Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ^ Walker, Susannah (23 Feb 2007). Style and Status: Selling Beauty to African American Women, 1920-1975. Academy Press of Kentucky. pp. 112, 125–. ISBN978-0-8131-2433-9 . Retrieved nineteen September 2012.

- ^ Sherrow, p. 365

- ^ Pomerance, Murray (26 October 2005). American Cinema of the 1950s. Rutgers University Press. pp. 10–. ISBN978-0-8135-3673-6 . Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ^ Toedt, John; Koza, Darrell; Cleef-Toedt, Kathleen Van (2005). Chemical Composition Of Everyday Products . Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 39–. ISBN978-0-313-32579-3 . Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ^ Dominguez, Pier (1 June 2003). Christina Aguilera: A Star Is Made. Amber Books Publishing. p. 218. ISBN978-0-9702224-5-nine . Retrieved xviii September 2012.

- ^ "David Beckham Fetes H&Yard Launch in London". Women'south Habiliment Daily. ii February 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ Broadhead, Julian; Kerr, Laura (i January 2000). Prison Writing 2001. Waterside Press. p. 20. ISBN978-1-872870-87-eight . Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ Jenkins, Ronald Scott (June 1994). Subversive laughter: the liberating power of one-act. Free Press. p. 147. ISBN978-0-02-916405-i . Retrieved xviii September 2012.

- ^ "» History of the Regent:: Néojaponisme » Weblog Annal". Retrieved 2016-03-18 .

External links [edit]

- Nigh famous hairstyles of the 1950s

0 Response to "Who Did Hair Fashion in the 50 and 60 1950s Hair and Makeup"

Post a Comment